12th–13th centuries

location: 42.29512431042163, 42.76809267550765

The Gelati Monastery, located on a mountain slope near the village of Gelati, near Kutaisi in western Georgia, is one of the most important monuments of medieval Georgian architecture and culture. Founded in 1106 by King David IV the Builder (Aghmashenebeli), who ruled from 1089 to 1125, the monastery stands as a symbol of the Georgian Golden Age. This period marked the peak of the political power of the Kingdom of Georgia, with the defeat of the Seljuk Turks and the recapture of Tbilisi from the Arabs, which led to the transfer of the capital from Kutaisi to Tbilisi. The Gelati Monastery is considered the most representative monument of this period, embodying both the political achievements and the cultural and architectural developments of the time.

King David envisioned Gelati not only as a place of worship, but also as an international center of learning, attracting prominent theologians and philosophers. It included a scriptorium and became a repository for valuable treasures such as icons and manuscripts. The importance of this foundation was underscored by a royal chronicler who referred to Gelati as a “second Jerusalem” and “another Athens,” emphasizing its significance as a spiritual and intellectual center. Today, the monastery complex consists of three churches, a bell tower and the remains of an academy building.

The first and main church of the monastery, the Church of the Nativity of the Virgin, was built between 1106 and 1130. The original church had a simple cross-in-square plan, with a high dome supported by massive interior piers, and was built of finely hewn stone blocks, with blind arcades as the main architectural decoration of the facades. In the 13th century, chapels were added to the north and east sides. The exterior of the church has a stepped hierarchy, with the highest parts being the arms of the church and the lowest parts being the chapels and the narthex.

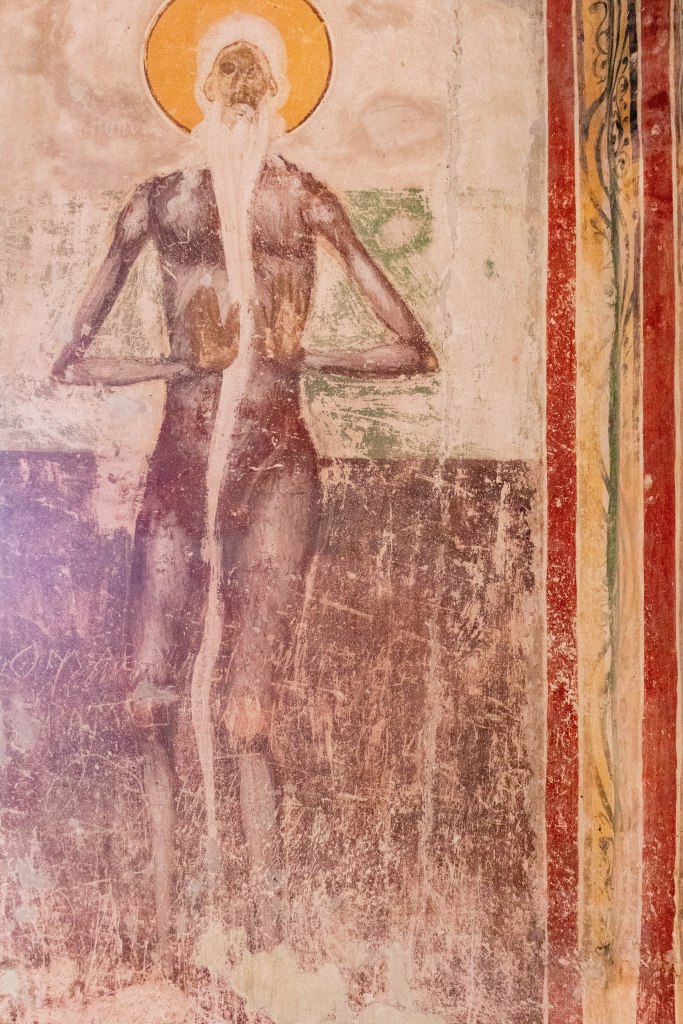

The interior of the church is especially noteworthy for its exceptional murals and mosaics. The mosaic of Virgin Nicopea, flanked by archangels and set against a golden background, was created between 1125 and 1130 and rivals the finest Byzantine works of its time. The frescoes of the same period are mostly preserved in the narthex, while the southeastern chapel and the southern porch have Palaeologan-style frescoes from the late 13th and 14th centuries.

The frescoes were severely damaged during the Ottoman invasions of 1509-1510. As a result, restoration work was commissioned by the kings of Imereti, including Bagrat III (1510-1565) and George II (1565-1583). This marked a major period of repair and decoration, which is why most of the murals date from the 16th century. Painting continued into the 17th century, with murals on the lower part of the western arm and in the northeast and northwest chapels.

In the 13th century, additional structures were built around the main church, including the Church of St. George, the two-story Church of St. Nicholas, and a bell tower. The Church of St. George, located to the east of the main church, contains murals painted between 1565 and 1583.

The Church of St. Nicholas, built at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries, is a two-storey building with a barrel-vaulted lower floor and a free-cross domed upper floor. To the west of the Church of the Nativity of the Virgin Mary and the Church of St. Nicholas are the remains of a 12th century academy, of which only the outer walls and a portico from the late 13th and early 14th centuries remain.

After being closed during the Soviet period in 1923, the monastery was reopened for monastic life in 1988. In 1994, the Gelati Monastery was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. However, despite its global significance, the monastery’s conservation efforts have been far from ideal. Since 2020, restoration efforts have focused primarily on preserving the murals in the main church, with UNESCO providing advisory support. However, disagreements between the Georgian Orthodox Church and UNESCO over restoration methods – particularly the frescoes – as well as issues related to the temporary roofing have caused significant delays.

Despite additional funding from the Georgian government in 2024, the construction of a temporary roof to protect the frescoes from water damage has suffered setbacks. As a result, the monastery has been closed to visitors for much of the year, including the summer months. As of late 2024, much of the restoration work remains unfinished, with the Church of St. George also suffering from moisture damage, and the monastery remains closed to the public most of the time.

Sources and Further Reading

For a detailed exploration of the Gelati mosaics, check out the special article with photos by Leila Khuskivadze, available at ATINATI

Khoshtaria, D. Medieval Georgian Churches: A Concise Overview of Architecture. Tbilisi, 2023.

Kimadze, T. How the Restoration of Gelati Became a ‘Mission Impossible’. Available at iFact

[no author] The Risk to Gelati’s Cultural Heritage: What Threats Arise from the Delay in Temporary Roofing? Available at iFact

Mikeladze, K. Gelati Monastery. Available at ATINATI

text and photos by Elena Lisitsyna