location: 41.685037213498696, 44.82780825341779

architects: Viktor Jorbenadze, Vazha Orbeladze

date: 1984

The photographs were provided by Pavel Ogorodnikov, who explores abandoned places in Georgia (IG: @pavelog) and curates an archive of Georgian mosaics (IG: @georgian_mosaic).

The Tbilisi Palace of Rituals, also known as Wedding Palace or Patarkatsishvili Palace, was conceived in the late 1970s, when wedding houses in Tbilisi primarily served as registration offices, lacking the grandeur and celebration typically associated with religious ceremonies in Georgian churches. With religious customs, especially those linked to Orthodox traditions, being suppressed under Soviet rule, these rituals had been diminished. Architect Viktor Djorbenadze sought to restore a sense of significance and splendor to these events, naming the building the “Palace of Ceremonies” rather than adhering to the typical Soviet marriage registry format. Djorbenadze, known for his work on the Mukhatgverdi Cemetery Complex (1972-1974), which also integrated a ceremonial hall, brought similar themes of ritual and communal significance to this project.

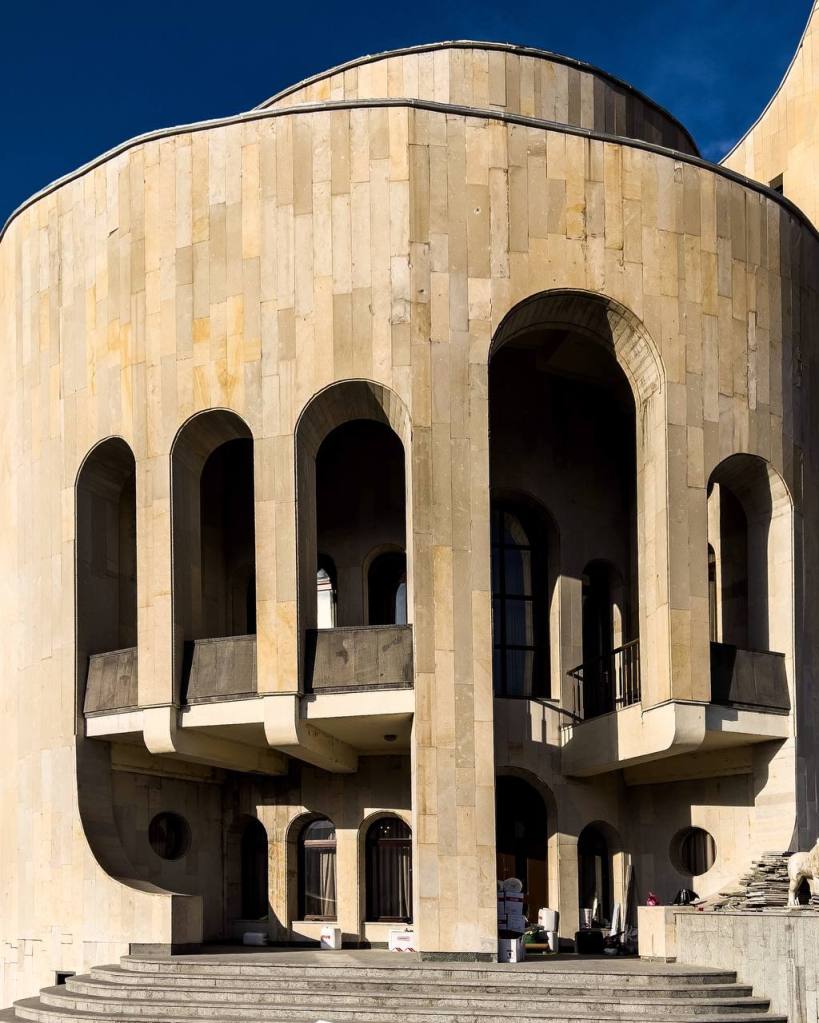

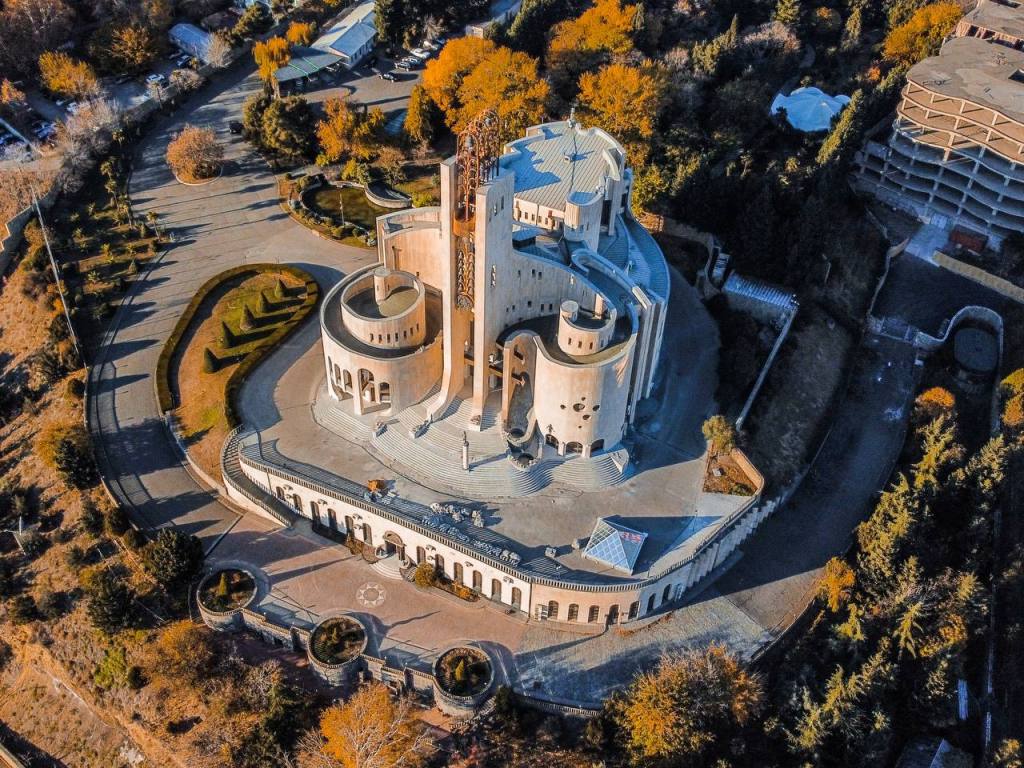

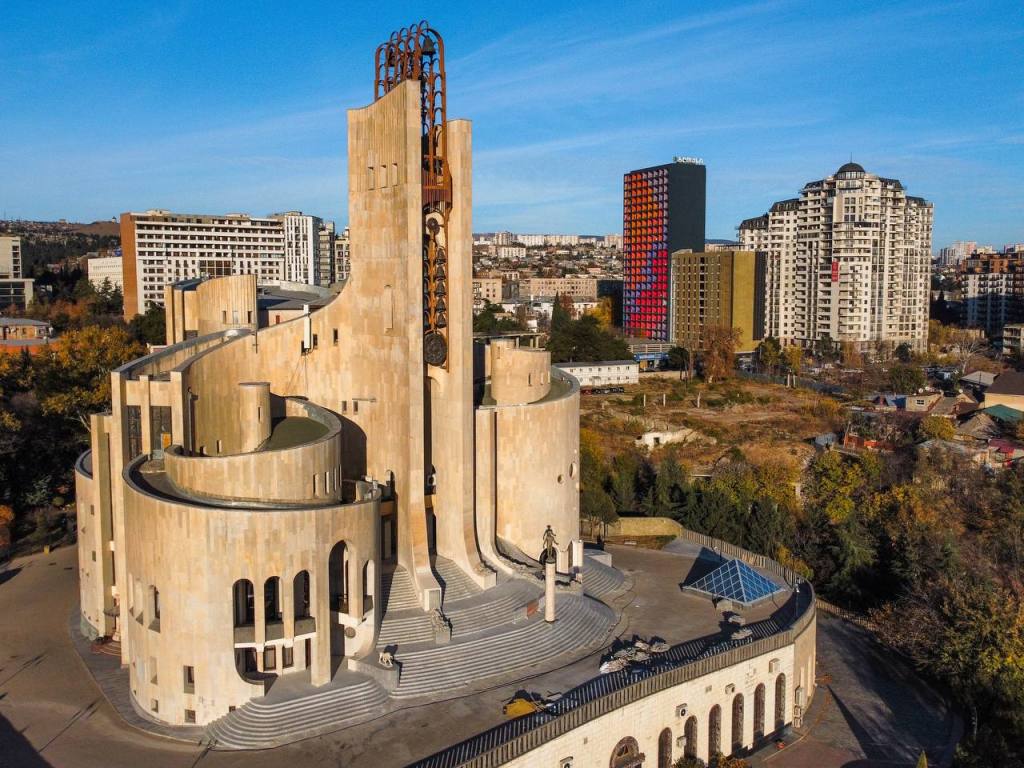

Work on the Palace began in 1979, with construction concluding in 1984. Situated on a hill near the Ortachala Hydropower Plant dam, the design, by Djorbenadze and architect Vazha Orbeladze, presents a striking fusion of modernism and neo-expressionism, while incorporating elements from both Georgian ecclesiastical and traditional house architecture. The result is an exceptional interpretation of Soviet modernist architecture, drawing clear inspiration from Le Corbusier’s later works, particularly the chapel at Ronchamp, which is known for its bold, sculptural forms.

Symbolism plays a central role in the Palace’s design. From the eastern and western perspectives, the building’s form evokes ancient Roman theaters or amphitheaters—spaces designed for public gatherings, much like the Palace, which was intended for large, festive weddings. However, unlike the simpler structures of antiquity, such as the Colosseum, the Palace’s construction is far more intricate, with its internal forms visibly extruded outward, aligning with key principles of modernist architecture.

Despite these classical references, the Palace is firmly rooted in late modernism, evident in its large spiral-shaped components. This design approach echoes Djorbenadze’s earlier projects, such as the Mukhatgverdi Cemetery Hall and the Ilia Chavchavadze Museum in Kvareli, where similarly round forms are reminiscent of the apses found in Orthodox churches, an enduring influence on the architect. This is particularly notable in the main façade, which features two large asymmetrical spiral forms, with a vertical tower at the center—a deliberate nod to a medieval cathedral’s bell tower.

Beyond its architectural nods to ecclesiastical and public buildings, the Palace’s design reinforces the sacredness of its purpose: as a temple of life and birth. At its heart, the building’s layout symbolically represents the anatomy of the female reproductive system. The Palace’s form, with its anatomical references and symbolic meanings, is not concealed by galleries or ornamental façades; instead, it reveals its structural complexity and significance in a direct and unapologetic manner.

Inside, the ceremonial hall continues the blend of symbolic elements. The hall is illuminated by stained glass windows and crowned by a dome-like structure, reminiscent of a temple’s drum. The wooden stepped pyramidal vault above mimics the traditional Georgian gvirgvini roof, creating a striking fusion of old and new. The layout emphasizes a sanctuary-like space, marked by two columns that separate it from the main hall, a like-an-altar table, and a large mural behind it—together evoking the sacredness of a church.

This connection is reinforced by the mural itself, painted by Zura Nizharadze. The artwork depicts a wedding procession, presided over by a central female figure, two times larger than the others. This figure can be interpreted as Mother Nature or Mother Georgia, or in the context of an officially atheist state, perhaps a secular representation of the Virgin Mary. The mural also weaves in elements of Georgian landscape, with depictions of Tbilisi, the Kura River, and iconic modernist buildings like the Dinamo Stadium. At its center is a miniature version of the Palace of Ceremonies itself, held aloft by a lion-headed figure—a likely metaphor for the architect, reminiscent of medieval frescoes that often depicted donors to the church.

Originally conceived as a ceremonial space, the Palace was converted in 2002 into the private residence of businessman Badri Patarkatsishvili. He undertook significant renovations, redecorating the lower rooms in various pseudo-styles, including Egyptian and Chinese themes, and creating a small courtyard designed to resemble Old Tbilisi. A garden with peacocks was also added, and in 2008, Patarkatsishvili was buried on the grounds. Today, the building remains privately owned, with restricted public access. However, it can still be rented for special events, such as weddings or banquets, and guided tours are occasionally available.

text by Elena Lisitsyna

photos by Pavel Ogorodnikov