location: 41.694123446860544, 44.7970845092238

date: 1877

illustration focus: street view

If you would like to discover Mtatsminda more in detail, our partner FAHU travel offers a walking tour of its historic streets and entrance halls, including a visit to a 19th-century apartment; more details here.

The corner house at 10/2 opens a quintessential Mtatsminda perspective: a sloping street where façades step with the relief and corners read as small urban pavilions. It succinctly embodies the 19th century Europeanised expansion on Tbilisi’s main hillside, laid out as a rectilinear network beyond the medieval core. The hill name “Mtatsminda” (“Holy Mountain” in Georgian) is medieval and tied to St. David’s hermitage; in the nineteenth century the term migrated from the hill to the quarter on its lower flank, and in the Soviet 1930s it became an administrative district. Under the Viceroy’s centralized oversight in the first half of the century – especially under Mikhail Vorontsov (1844–1853) – the urban fabric was regularised and the public realm consolidated, culminating mid-century in the landscaped Alexander Gardens (1859; today April 9 Park) and the maturation of Golovinsky (now Rustaveli) Avenue as the city’s principal showcase axis.The transport armature locked in with the horse-tram (1883) and electric trams (1904–1905). Early twentieth-century landmarks – the funicular (1905) and, later, the formalised Mtatsminda Park (1920s–1950s) – completed the hill’s civic silhouette above the 19th century grid.

Residential infill intensified in the 1870s–1890s: two- to three-storey revenue houses stepped with the gradient, presented “European” fronts to the street, and turned domestic life to yards and timber galleries. Ingorokva Street (historically known as Laboratornaya) belong squarely to this wave. The streetscape remains a stepped run of masonry fronts and emphatic corners, aligned to the grid yet fine-tuned to the slope. In our illustration with no. 10/2 in the foreground and façades descending toward the lower blocks, the panorama reads like a textbook of the period’s urban project: rusticated bases, firm cornice lines, later iron balconies, and a crescendo of ornament as one descends.

As for no. 10/2 itself, commission is linked to Anton Sogomonovich Korganov (Arm. Korganants/Korganian), banker and public figure. The family name appears in Russified form (“Korganov”) in imperial records, a standard practice of the time. In the twentieth century, local memory ties the building to theatre director Kote Marjanishvili; a metal plaque on the façade records his residence and keeps that association in public view.

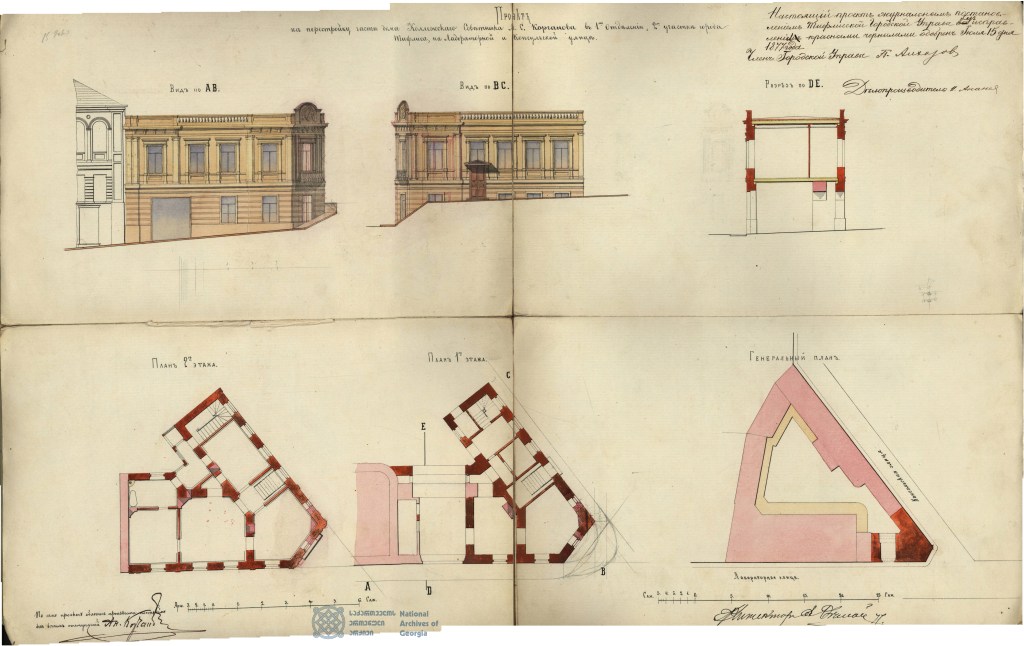

The house at no. 10/2 is a three-storey brick corner building set over a semi-basement on the falling line of the street (i.e. ground floor). Its late-classical order reads in the pilasters pacing the principal window bays and in the firm attic parapet that turns the corner like a small pavilion. Helpfully, an archival project sheet survives: it envisages only two storeys (the lower as a semi-basement on the slope), crowned by a more emphatic attic with a balustrade and a rusticated ground floor. In execution the building gained an extra storey, yet the façade was simplified: the attic was kept but without stucco enrichment, the balustrade was not realised, and the ground-floor rustication was omitted, while the pilaster rhythm of the upper storeys remained. A further nuance is visible on the general plan: a separate building already stood to the left along Laboratornaya; today that volume is physically joined to the corner house and registered as part of no. 10, although it was originally a distinct structure.

archival plan explanation

The permit sheet contains the standard late-imperial set: a street elevation, floor plans, a longitudinal section, and a small site sketch showing the building lines at the corner of Laboratornaya (today Pavle Ingorokva) Street and of Konsulskaya (today Peter Chaiakovski) Street. On this sheet, red indicates masonry cut in plan/section; yellow marks timber elements; pink denotes elements beyond the cut or neighboring property.

To experience the street as a compact walking lesson, move downhill from 10/2. At no. 8 (1914), a severe late-imperial façade by Christopher Ter-Sarkisov (Arm. Ter-Satunts) announces “official” Tbilisi: for a time it housed the Office of the Governor in the Caucasus and today it is home to the Arnold Chikobava Institute of Linguistics.

No. 6 on Pavle Ingorokva Street in fact consists of two attached houses; the longer right-hand block is often listed separately as No. 6a. Built in 1888 as a pseudo-Renaissance income house, it has rich plasterwork from mascaron keystones to an ornate bracketed cornice and parapet. On the courtyard side, timber gallery-balconies — originally with stained-glass — served enfiladed rooms typical of Tbilisi income houses, though the layout and interiors have been heavily altered.

The shorter left-hand part of No. 6 is the Ivan Tairov residence (project by Aleksander Szymkiewicz, 1887–1900), famed for its “devilish” mascarons – a satyr among them – above a richly modelled entrance. In the 1890s–1920s it also became a cultural address, hosting the Armenian women’s charitable society and later the “Ayartun” house of arts associated with Hovhannes Tumanyan’s circle, before Soviet reorganisation turned the ensemble into housing.

No. 4 is earlier and quieter (early 1850s), with an 1858 permit for wooden balconies and a metal gate recorded under Asatur Khalatov and designs by Grigol Ivanov. It is a plain three-storey brick dwelling with basement and an inner yard of timber galleries. Actually, the house is one of the street’s oldest domestic fronts and now is in need of careful restoration.

At no. 2, the descent of Ingorokva street closes on ornament: richer stucco frames, cartouches, and additional mascarons create a small finale that rewards looking up along the cornice line. This late 19th century building was an income house of the Prince Nikolai Tumanov/Tumanishvili (Arm. Tumanyan).

Ingorokva concentrates Mtatsminda in miniature: a European street face and an inward, gallery-bound life, set on a slope that choreographs façades into a single perspective. Begin at 10/2 to read the type, then follow the street downhill—the sequence becomes a short, memorable tour of Tbilisi’s late-imperial city-making.

Sources and Further Reading

National Archives of Georgia (NAG). Fond 192. Series 8a. File 63.

Beridze, Vakhtang. Architecture of Tbilisi, 1801–1917, 2 vols. [tbilisis khurotmodzghvreba, 1801–1917]. Tbilisi, 1960–1963. [in Georgian]

Chanishvili, Nino. Asatur Khalatov Building (online entry). Available at: metaport.ai

Kvirkvelia, Tengiz. Old Tbilisi [dzveli tbilisi]. Tbilisi, 1984. [in Georgian]

Kutateladze, Tea. Interiors of Residential and Public Buildings in Tbilisi, 19th–20th Centuries [satskhovrebeli da sazogadoebrivi shenobebis int’erierebis monument’ur-dek’orat’iuli perts’era k. tbilisshi XIX-XX sauk’uneebis mijnaze]. Tbilisi, 2015. [in Georgian].

Meskhi, Maia. Architectural-feature Analysis, Problems and Paradigms of Sololaki Area’s Spatial-Volumetric Structure [sololak’is sivrtsit – motsulobiti st’rukt’uris arkit’ekt’urul – mkhat’vruli analizi, problemebi da paradigmebi. Tbilisi, 2019. [in Georgian].

[Sargis Darchinyan Archive] Ivan Tairov Residence (online entry). Available at: metaport.ai

Tavadze, Tamar. Anton and David Korganov Building (online entry). Available at: metaport.ai

Tavadze, Tamar. Prince Nikolai Tumanov Property (online entry). Available at: metaport.ai

Tavadze, Tamar. The Office of the Governor in the Caucasus (online entry). Available at: metaport.ai

Tsintsadze, Vakhtang. Tbilisi: Architecture of the Old City and Residential Houses of the First Half of the 19th Century [Tbilisi. Arkhitektura starogo goroda i zhilye doma pervoi poloviny XIX stoletiia]. Tbilisi, 1958. [in Russian]

Wheeler, Angela. Architectural Guide: Tbilisi. 2023.

text and photos by Elena Lisitsyna