location: 41.70755284625875, 44.80222577978583

date: 1896

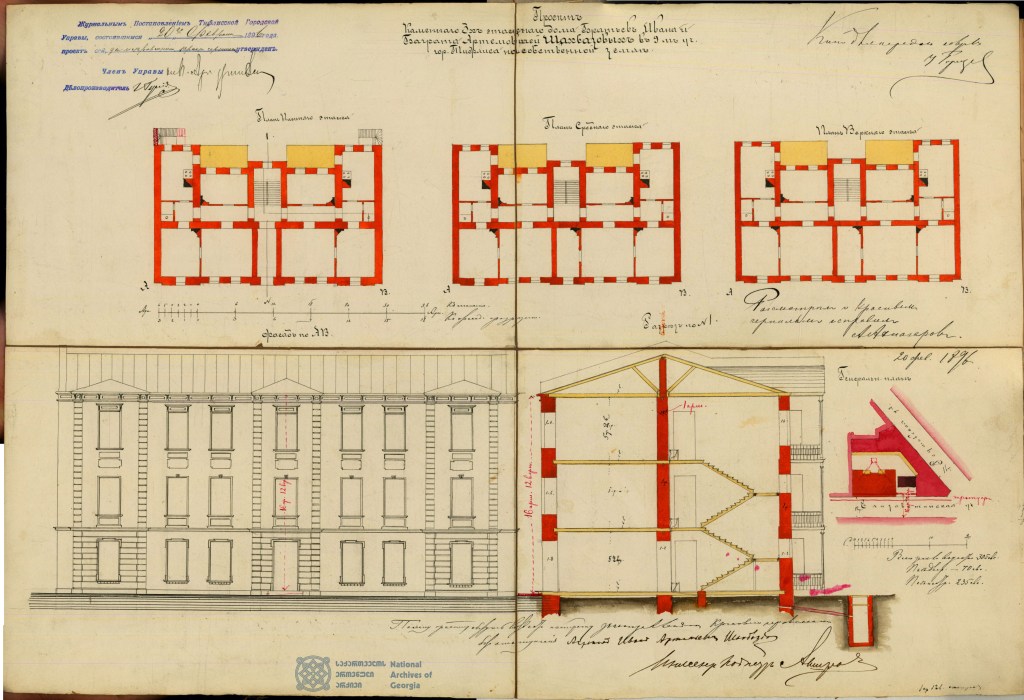

illustration focus: courtyard elevation; external wooden staircase

If you would like to explore Chugureti beyond this building, our partner FAHU travel offers a walking tour of the district’s entrance halls, including a visit to the former Apollo cinema; more details here.

The tenement at 49 Tsinamdzgvrishvili Street stands slightly back from the street at the diagonal meeting with Mazniashvili, so that its side elevation reads almost like a second façade across the small corner square. Archival drawings date the project to 1896 and name the clients as the brothers Ivan and Bagrat Shakhbazov—very likely of Azerbaijani origin, judging by the family name. An ownership trace resurfaces in the press: the newspaper Kavkaz (19 May 1911) carried a notice of auction for arrears concerning the Shakhbazovs’ real estate—namely this house on then-Elizavetinskaya Street.

The urban setting belongs to today’s Chugureti district, historically known as Kukia on the left bank of the Kura River. This area became a gridded suburb during the organized settlement of German colonists in 1817–1819, hence the nineteenth-century labels “Tiflisser Kolonie” and “Neu-Tiflis.” Over the century, modest German houses on elongated plots gave way to larger revenue houses. Integration with the city accelerated after the Transcaucasian Railway depot opened in Chugureti in 1872, drawing an ethnically diverse population and new trades. In period sources the two bounding streets are Elizavetinskaya (now Tsinamdzgvrishvili) and Reutovskaya/Reut Street (now Mazniashvili) – the latter laid out in 1846 under General-Lieutenant Joseph Reut and distinctive for its diagonal cut across the Kukia grid.

From the street, No. 49 does not immediately stand out. Its interest lies in the courtyard elevation and the triangular shared yard formed with 10 Mazniashvili because of the latter’s diagonal approach. On the building’s central axis rises a distinctive stair tower: a fully covered, three-storey external wooden stair whose opposed flights read as a rhomboid figure.

In general, external stairs were common in nineteenth-century Tbilisi—spiral or corner stairs especially—because they freed interior space; some were shaped to lend a festive air to the yard. The axial stair here is the rare, emblematic variant. As Maia Mania notes, the flights are carried on diagonally set stair stringers (Ger. Treppenwange), with parts of the volume fixed to the courtyard’s bearing wall; the tower thus stitches the galleries together and, in places, projects beyond their plane. The building wraps the yard in an L-plan, with rooms and galleries opening to the shared space; the three-bay wooden galleries along the stair are now enclosed as shushabandi (glazed timber loggias typical of Tbilisi courtyards). Much of the fretworked railing has been lost, but the composition remains legible. Notably, the 1896 official house plan shows only continuous balconies: the stair’s absence suggests a slightly later addition by local craftsmen. A related (though differently arranged) example survives nearby at 29/13 Davit Kldiashvili Street.

The street front adopts a consciously late-nineteenth-century “European” mix: a rusticated ground floor; flat-arched ground-floor windows marked by small keystones; simple triangular crowns over the first-floor windows; and straight-topped second-floor windows with a slim brick cap line. The façade is lightly stepped into shallow risalits framed by narrow brick pilasters on the first and second floors, and a bold top cornice finishes the front.

Characteristic, too, is the façade’s polychromy – alternating bright red brick with grey plaster imitating flat stone – which sharpens the relief of projecting elements. Because the neighboring house at No. 51 is only one storey high and the corner opens into a small square, the east side elevation is unusually exposed in the streetscape. Inside the entrance hall, the main stair alternates timber with cast-iron balustrade panels of scrolling volutes, a late-imperial motif encountered across Tbilisi.

The surviving set from the historical archive includes a site plan, three floor plans, a street elevation, and a longitudinal section; the author’s signature is hard to read. The drawn scheme is symmetrical – central entrance and stair, one apartment on either side per floor, continuous timber balconies to the courtyard on all three storeys. In reality, the built ensemble diverges, and not only in the absence of the central axial stairs. In the courtyard elevation, the galleries/balconies are shown open rather than glazed – glazing likely occurred after completion. More discernible are differences on the street façade: it is clear that the central bay was planned to project like the shallow side bays, but this was not realised. As for rustication, it was planned only on the projecting parts of the ground floor, but was executed across the entire ground-floor façade. However, such deviations were common in Tbilisi residential architecture when one compares designs approved by the Tiflis City Administration with the houses as built.

Seen within the broader evolution of Tbilisi housing, No. 49 condenses a familiar duality: a Europeanised public face to the street and social-domestic life organized around timber galleries and open circulation in the yard. This “inner side,” unlike the “front side,” was less governed by official taste and more open to local craftsmanship, which often took the form of open or later glazed balcony-galleries. From the 1830s onward, such galleries became a defining social space of Tbilisi’s residential architecture; here, however, the rare axial stair intensifies that effect, turning the interior court into a small landmark in its own right. Even today the building carries traces of its long life in the weathered masonry: a vertical crack, reported by residents as an after-effect of the 1988 Spitak earthquake, runs down a plastered wall in the yard. Unfortunately, the overall condition of the house remains poor and unrestored despite its protected status (the building is registered as an immovable cultural heritage monument of Georgia, no. 5267).

Sources and Further Reading

Georgian National Archive. Fund 192. Series 8A. File 4962.

Ministry of Culture and Sports of Georgia. Heritage Passport for 49 Mikheil Tsinamdzgvrishvili Street (Register No. 5267). Available at: memkvidreoba.gov.ge

Beridze, Vakhtang. Architecture of Tbilisi, 1801–1917, 2 vols. [tbilisis khurotmodzghvreba, 1801–1917]. Tbilisi, 1960–1963. [in Georgian]

Chanishvili, Nino. Nineteenth-Century Architecture of Tbilisi as a Reflection of Cultural and Social History of the City. FaRiG Rothschild Research Grant Report, 2007.

Kavkaz [Кавказ]. Newspaper notice of auction for the Shakhbazov brothers’ property, 19 May 1911. [in Russian]

Kvirkvelia, Tengiz. Old Tbilisi [dzveli tbilisi]. Tbilisi, 1984. [in Georgian]

Kutateladze, Tea. Interiors of Residential and Public Buildings in Tbilisi, 19th–20th Centuries [satskhovrebeli da sazogadoebrivi shenobebis int’erierebis monument’ur-dek’orat’iuli perts’era k. tbilisshi XIX–XX sauk’uneebis mijnaze]. Tbilisi, 2015. [in Georgian]

Mania, Maia. “Architectural and Art Historical Review of a Former Tenement House at 49

Tsinamdghvrishvili Street and its Surrounding Quarter”, in: Tsinamdzgvrishvili 49 / Mazniashvili 10. Tbilisi, 2023.

Tsintsadze, Vakhtang. Tbilisi: Architecture of the Old City and Residential Houses of the First Half of the 19th Century [Tbilisi. Arkhitektura starogo goroda i zhilye doma pervoi poloviny XIX stoletiia]. Tbilisi, 1958. [in Russian]

Wheeler, Angela. Architectural Guide: Tbilisi. 2023.

text and photos by Elena Lisitsyna